What Marcel Lapierre & Paul Cézanne Had in Common

How a painter and a winemaker helped reshape art and wine by challenging tradition.

Written by Sophie Stuart

Illustration by Cerise Zelenetz

Wine and art have existed for thousands of years, and without them, life would arguably be far less enjoyable. The connections between the two are infinite. Take the post-impressionist painter Paul Cézanne and Beaujolais winemaker Marcel Lapierre—two French revolutionaries separated by decades. What could a painter and a winemaker have in common?

Pursuing his dream to become a professional artist, Paul Cézanne moved from his hometown of Provence to Paris. Known for being a bit eccentric and enigmatic, Cézanne was singular in his approach to painting. Desperate to further his artistic career Cézanne applied to art schools and well-known galleries but was never admitted––rejected by traditionalists for his unconventional approach. He spent his days at the Louvre, studying and sketching masterpieces, including those of Michelangelo. During this time, Cézanne formed a close mentorship with other notable artists like Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet.

Cézanne’s work is often described as alive, energetic, and vivid, and he famously said, “we must not paint what we think we see, but what we see.” While this might seem obvious, it was noteworthy at the time. In the 1800’s, movements like realism and romanticism were thriving––hyper-realistic or embellished still lifes and portraits. Paintings like Cézanne’s that displayed beauty and flaws were far from favorable. By forging his own path, young artists that soon followed like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse saw Cézanne’s work and hoped to emulate it.

Categorized as post-impressionism or pre-modernism, it’s hard to put Cézanne in a singular category. It’s well documented that Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse called Cézanne “the father to us all.” Meaning the father of Cubism and Fauvism – movements that shaped the post-impressionism and modern art movements.

Decades later, in 1973, Marcel Lapierre found himself at a similar crossroad in Beajoulais. He had inherited his family’s domaine and had become disillusioned with Beaujolais wine. Particularly, Beaujolais Nouveau – the young, bubblegum and fruity Gamay was infamous. Eager to find a way to improve and showcase the terroir he grew up with, he adopted a philosophy that embraces organic farming and low-intervention winemaking, under the guidance of skilled chemist and wine négociant, Jules Chauvet.

Influential wine importer, writer and retailer Kermit Lynch famously described Lapierre as a key figure in the “Gang of Four”––a group of winemakers, including Guy Breton, Jean-Paul Thévenet, and Jean Foillard, who rejected commercialized practices to help redefine the region’s identity.

It’s hard to overstate the impact Lapierre had on the low-intervention wine movement, which is loved dearly and imbibed today. While Lapierre’s methods harkened back to the origins of winemaking, they were considered rebellious at the time.

So this brings us back to the original question––what did the famous painter, Paul Cézanne, and celebrated winemaker, Marcel Lapierre, have in common?

Both Cézanne and Lapierre were unconventional in pursuing the work they believed in––and it paid off. Major movements in both art and wine production emerged because these two individuals followed a path that was authentic to themselves.

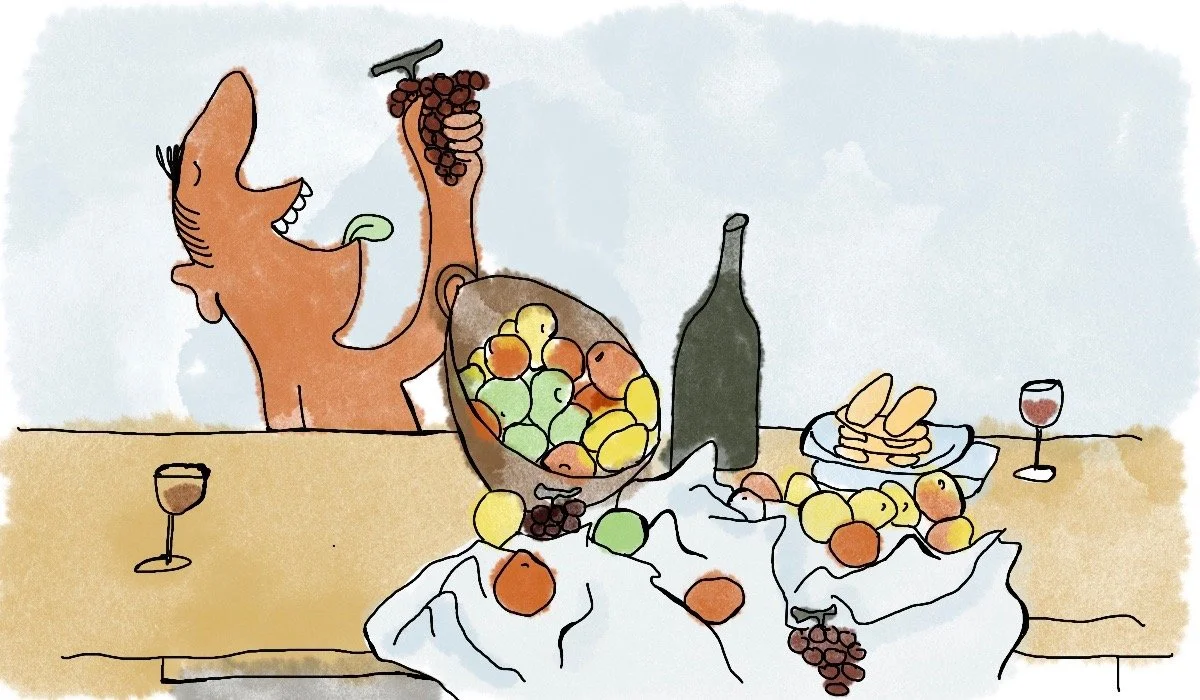

One of Cézanne’s most famous pieces is The Basket of Apples, created in 1893. A seemingly basic still life of… drumroll please… a basket of apples. There are no right angles in this painting, a remarkable detail in the late 1800’s art world. The thick brushstrokes and basket angled up and forward elicit the heavy weight of the objects. The movement of the light is evocative, almost like the light is dancing off the canvas. At the time, still lifes looked like hyper-realistic, impassive photographs. Coincidentally, this painting was one of the first displayed in Paris after Cézanne gained notoriety as an established painter.

Comparing this to Lapierre’s well-known cuveé Raisins Gaulois. With its screw-top and cartoon-like figure eating a handful of grapes, the cuvée is accessible in every way. When talking about the idea of Raisins Gaulois to Kermit Lynch, Lapierre said, “It’s a wine you drink like a beer…when you don’t really want to drink a beer.” Raisins Gaulois has a glou-glou, playful quality, while also complex and alive; displaying some of the best characteristics of Gamay from Beaujolais.

Raisins Gaulois and Basket of Apples are approachable and dynamic––unusual characteristics in otherwise intimidating subjects. Both Cézanne and Lapierre could make work that may at first seem rudimentary, but with time, the impact of their pieces are everlasting.

As an art history student, I was immediately mesmerized by the connections between Cézanne’s work and that of more widely known artists like Pablo Picasso. Without Cézanne’s groundbreaking vision, it’s hard to imagine Picasso’s cubist masterpieces coming into existence.

Marcel Lapierre’s wines have had the same impact on contemporary wine production. Now, years into my wine career, I can still recall the first time I drank Raisins Gaulois. I was eager to drink wine by the pioneering “Gang of Four” member and Raisins Gaulois was what I could find in the market. It was cheery with bright cranberry and subtle lilac notes that were forever changing in the glass. The cuvée was jubilant yet puzzling, still memorable today.

The impact Paul Cézanne and Marcel Lapierre have had on art and wine is immeasurable. As bold nonconformists, they sparked revolutions in their crafts, leaving legacies that continue to inspire and teach us today.

Émile Bernard once said of Paul Cézanne, “The painter gives concrete expression to his sensations, his perceptions, by means of line and color.” The same could be said of Marcel Lapierre, whose work, like Cézanne’s, bursts with endless tenacity, joy, and hope.